Music Theory: Understanding Key Signatures and Tonality

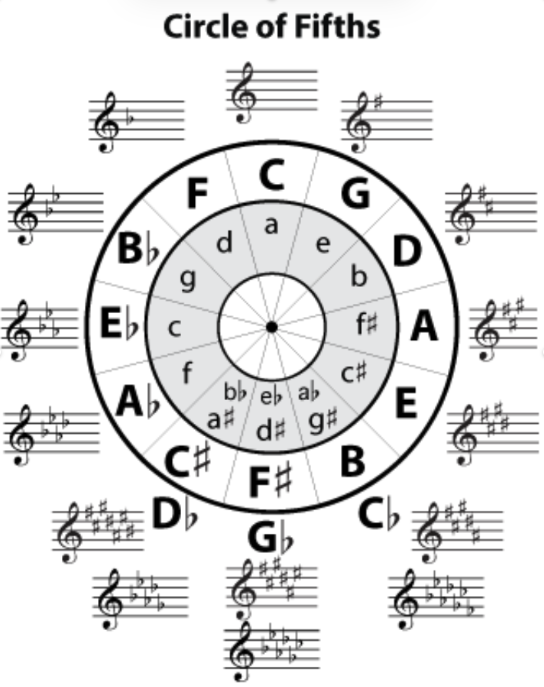

In our last lesson, we explored the Circle of Fifths and learned that there are twelve major and twelve minor keys, each defined by a unique key signature. For many students, memorizing these can be challenging. Is there a shortcut to help remember all the major and minor keys? And how are these key signatures connected?

Today, we’ll dive into how music theory reveals patterns in major keys.

Sharp keys signature

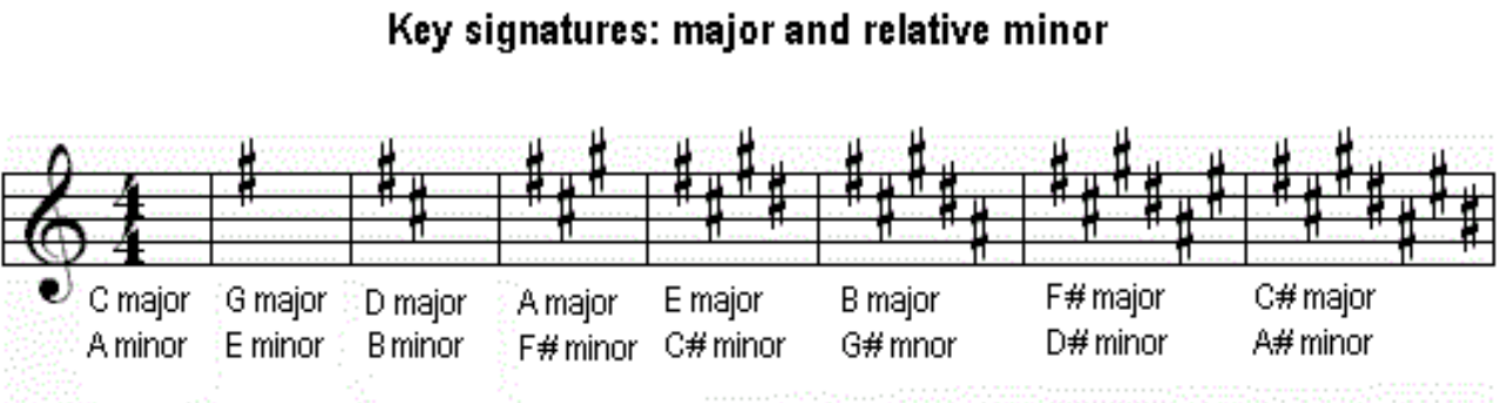

We begin with sharp keys. These are key signatures that contain sharps (#), increasing in number from one up to seven, as seen in the visual chart.

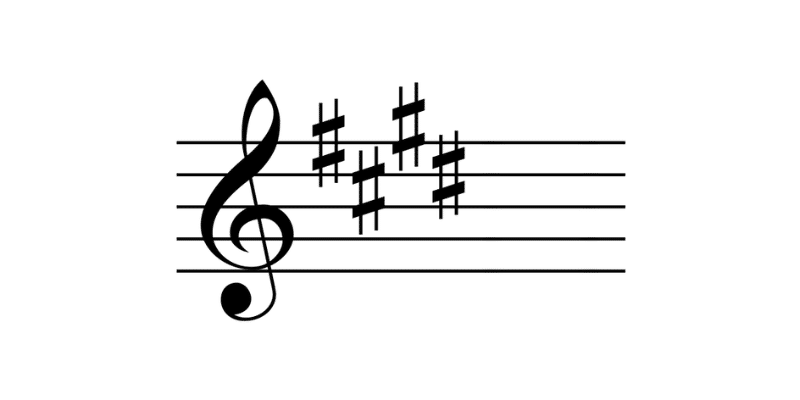

To interpret sharp key signatures, read from left to right, just like reading text. For instance, in this example:

The order of sharps is F#, C#, G#, D#.

The first rule for sharp key signatures is: Each added sharp is a perfect fifth above the previous one.

Let’s unpack this using examples. Begin with the first sharp, F♯, followed by the second, C♯.

Although they appear reversed on the staff, by adjusting F# down an octave, the interval between them becomes a perfect fifth—something we previously covered in music theory basics.

The pattern continues: From C# to G#, the distance is again a perfect fifth. (C–D–E–F–G).

This rule remains consistent even in the piano scale that contains all seven sharps. When notes appear lower, just shift the octave to make the fifths clearer.

Once you know the key signature, how do you determine the key name?

The second rule: In sharp keys, raise the last sharp by a half step to get the major key.

Let’s try it. This key signature has two sharps: F# and C#. The final note is C♯, and when raised by a half step, it becomes D. That means the key is D major.

One more: With five sharps—F#, C#, G#, D#, and A#—the last is A#. Go up a half step and you get B, so the key is B major.

Flat key signatures

Flat key signatures use the symbol (♭) and also range from one to seven flats. As with sharps, flats follow their own pair of rules.

The first rule in flat keys is the reverse of sharp keys: Each new flat is a perfect fifth below the one before it.

Example: Compare the first flat (Bb) with the second (Eb). This interval is a perfect fifth going downward, following the same music theory principle.

And yes, even the piano scale with all seven flats follows this rule. Again, adjust the octave if needed to maintain consistent fifths.

The second rule for flat key signatures: The second-to-last flat gives you the major key name—except for F major, which is the one exception.

Try this one: A key signature with Bb, Eb, and Ab. The second-to-last flat is E♭, indicating that the key is E♭ major.

One more: With six flats (Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb), the second-to-last is Gb, making the key Gb major.

Now, how do minor keys fit in?

Minor keys are directly linked to major keys in the Circle of Fifths. They have identical key signatures and are known as relative keys. The circle clearly displays these key pairs, typically placing major keys on the outer ring and minor keys on the inner ring.

You can find the relative minor key by lowering the major key by a minor third.

For example: If the key signature has two flats (Bb and Eb), the major key is Bb major. Drop it down a minor third, and you land on G. So, the corresponding minor key is G minor.

The relationship between major and minor keys, along with how sharps and flats build across the piano scale, all tie back to the elegant logic of music theory.